The Effects of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy on Health

Gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT), also known as cross-sex hormone therapy, involves the administration of sex hormones—oestrogen with anti-androgens for transfeminine individuals, or testosterone for transmasculine individuals—to align secondary sexual characteristics with gender identity. This post examines the documented physiological effects and mental health outcomes based on available clinical evidence.

Definition and Treatment Protocols

Gender-affirming hormone therapy encompasses two primary treatment pathways:

Feminising hormone therapy typically consists of oestradiol (administered orally, transdermally, or by injection) combined with anti-androgens such as spironolactone (common in the United States), cyproterone acetate (used in Europe and Asia but not FDA-approved in the US), or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists[1]. The goal is to suppress endogenous testosterone whilst providing physiological female-range oestrogen levels.

Masculinising hormone therapy involves testosterone administration (intramuscular, subcutaneous, or transdermal) to achieve physiological male-range testosterone levels whilst suppressing endogenous oestrogen production[2].

Current clinical guidelines, including those from the Endocrine Society and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), recommend comprehensive psychological assessment prior to treatment initiation, though specific requirements vary by jurisdiction[3].

Historical Development and Growth in Use

Whilst gender-affirming interventions for adults began in the early-to-mid 20th century, standardised protocols for adolescent treatment emerged in the Netherlands in the 1990s. The "Dutch protocol", first published in 1998, involved pubertal suppression with GnRH agonists at Tanner stage 2-3, followed by cross-sex hormones around age 16[4].

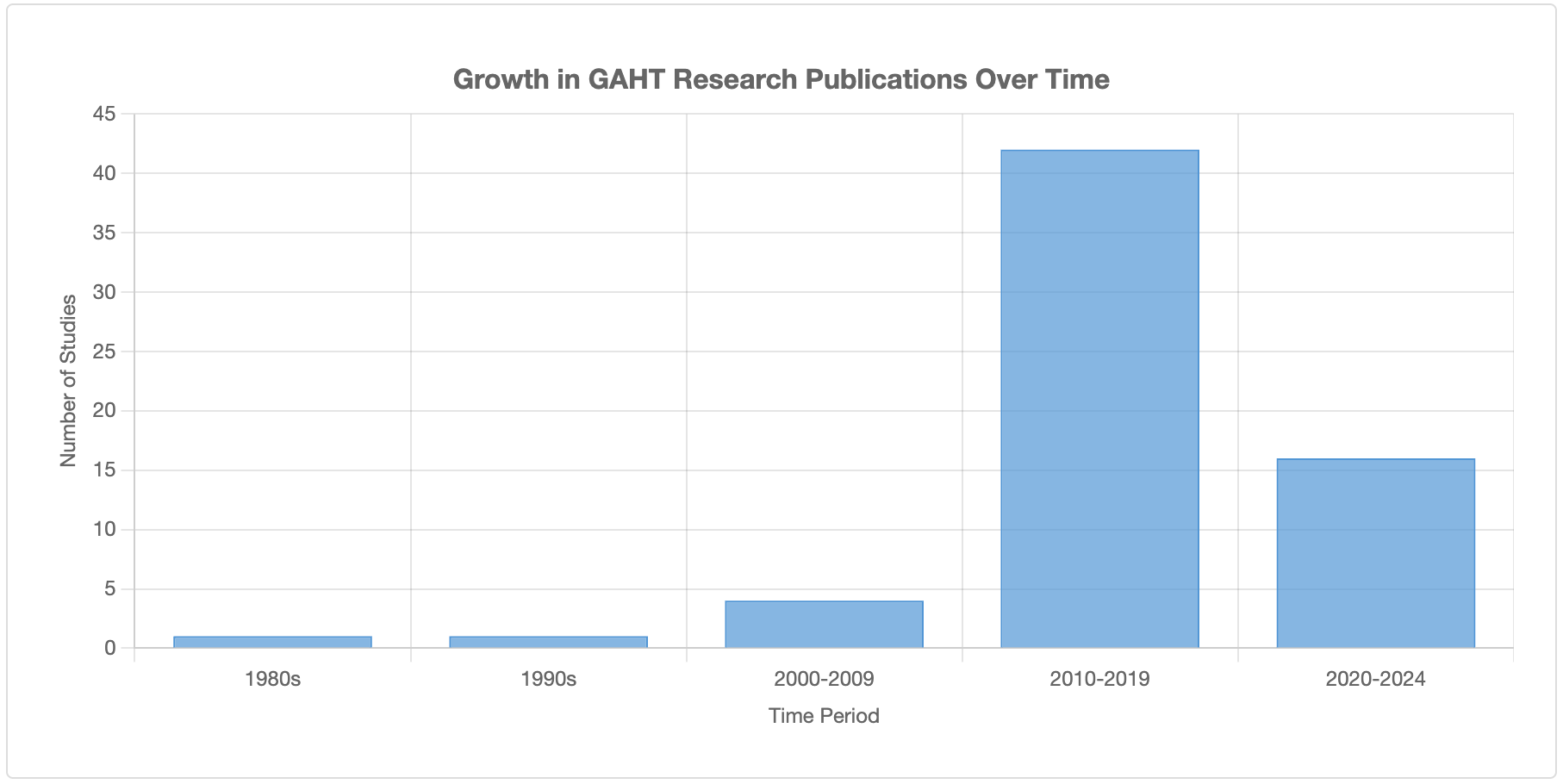

The prevalence of GAHT use has increased substantially in recent decades:

Research on this topic was sparse in the 1980s-1990s (only 1-2 studies per decade), increased moderately in 2000-2009 (4 studies), and proliferated after 2010 (82% of all studies conducted between 2010-2019)[5].

In the United States, approximately 0.6% of adults (1-1.4 million) and 2% of high school-aged individuals (150,000-300,000) identify as transgender[6].

Among commercially-insured US adolescents aged 8-17, fewer than 0.1% (approximately 1 in 1,000) received GAHT between 2018-2022, with 926 receiving puberty blockers and 1,927 receiving hormones during this period[7].

No patients under age 12 were prescribed hormones, suggesting clinical caution regarding age-appropriate initiation[7].

The prevalence of GAHT use has increased substantially in recent decades

Documented Cardiovascular and Physical Side Effects

A substantial body of clinical research documents physiological changes and risks associated with GAHT. The evidence quality varies, with most data derived from observational studies rather than randomised controlled trials.

Cardiovascular Effects in Transfeminine Individuals

Multiple studies indicate increased cardiovascular risk among transfeminine individuals receiving oestrogen therapy:

Myocardial infarction and stroke: Current evidence suggests that oestrogen use confers increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and ischaemic stroke compared to cisgender female reference populations, though findings are inconsistent when compared to cisgender males[8][9]. A Dutch cohort study of 2,517 transfeminine individuals found increased rates of MI and ischaemic stroke compared to cisgender women, though the absolute risk remained relatively low[10].

Venous thromboembolism (VTE): Transfeminine individuals face markedly elevated VTE risk. Oral ethinyl oestradiol carries an approximately 20-fold increased risk of spontaneous VTE[11]. Nearly all VTE cases occurred with oral oestrogen; transdermal oestradiol appears to confer lower risk[12]. Current formulations preferentially use oestradiol valerate over ethinyl oestradiol due to improved safety profile[11].

Lipid profile changes: Meta-analyses reveal significant alterations in lipid profiles, though clinical implications remain unclear. Oral oestrogen increases triglycerides (particularly after 24+ months of therapy), whilst transdermal oestrogen may decrease triglycerides. Effects on LDL-C, HDL-C, and total cholesterol are inconsistent across studies[13][14].

Cardiovascular Effects in Transmasculine Individuals

Evidence for cardiovascular risk in transmasculine individuals is less conclusive:

Blood pressure and lipids: Testosterone therapy produces atherogenic lipid changes and modest blood pressure elevations. However, despite these alterations, convincing evidence of increased cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease is lacking[8][9].

Haematological changes: Testosterone significantly increases haemoglobin (mean difference +1.48 g/dL) and haematocrit (mean difference +4.39%), raising blood viscosity. These changes could theoretically increase thrombotic risk, though thromboembolic events were not reported in reviewed studies[15].

Other Physiological Effects

SystemTransfeminine (Oestrogen)Transmasculine (Testosterone)Bone healthPositive correlation with trabecular bone score and lumbar bone mineral density; effects elsewhere inconsistent[9]Effects on bone mineral density remain poorly characterisedFertilitySuppression of spermatogenesis; reversibility uncertain after prolonged useSuppression of ovarian function; reversibility uncertain after prolonged useMetabolicPotential effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivityPotential effects on glucose metabolism; increased prevalence of polycystic ovarian syndrome-like features

Note: Most cardiovascular studies are observational with significant limitations: heterogeneous hormone regimens, variable follow-up periods, lack of randomised controls, and confounding by lifestyle factors including higher smoking rates, lower exercise rates, and pre-existing comorbidities that may be under-diagnosed and under-treated in transgender populations[16][17].

Mental Health Outcomes: Evidence and Limitations

Mental health outcomes represent the most contentious aspect of GAHT research. Transgender individuals experience disproportionately high rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation compared to cisgender populations, attributed to gender dysphoria, minority stress, discrimination, and social stigma[18][19].

Studies Reporting Positive Associations

Several studies report mental health improvements following GAHT initiation:

A prospective cohort study of 104 transgender and non-binary youth (ages 13-20) found 60% lower odds of depression (aOR 0.40, 95% CI 0.17-0.95) and 73% lower odds of suicidality (aOR 0.27, 95% CI 0.11-0.65) among those who initiated puberty blockers or hormones compared to those who did not, after adjustment for temporal trends[20].

A cross-sectional survey of 11,914 transgender youth found that those receiving GAHT who wanted it had lower rates of depression and past-year suicide attempts compared to those who wanted but did not receive GAHT[21].

A 2025 study of 342 adults initiating GAHT via telehealth found significant reductions in depression (PHQ-9 score reduction of -2.4) and anxiety (GAD-7 score reduction of -1.5) over 3 months. Among those with baseline suicidal ideation, 60% reported none at follow-up[22].

A systematic review of 46 studies (1980-2022) found consistent evidence for reductions in depressive symptoms and psychological distress following GAHT, though evidence for quality of life improvements was inconsistent[23].

Critical Methodological Limitations

Despite positive findings, systematic reviews and critical analyses identify severe limitations in the evidence base:

Study design weaknesses:

85% of studies in one systematic review had moderate, high, or serious risk of bias[24].

The vast majority of research consists of uncontrolled observational studies, cross-sectional surveys, or prospective cohorts without comparison groups[25].

No randomised controlled trials assess mental health outcomes of GAHT (such trials would face significant ethical and practical challenges).

Short follow-up periods: Most studies assess outcomes over 3-12 months; very few extend beyond 2 years. Long-term outcomes (10+ years) remain poorly characterised[23][26].

Confounding factors: Studies rarely adequately control for:

Concurrent psychiatric treatment (only 3 of reviewed studies accounted for psychiatric care)[25]

Social transition and family support (both strongly associated with mental health outcomes independent of medical intervention)[27]

Minority stress and discrimination

Selection bias (those who access GAHT may differ systematically from those who do not)

Inconsistent measurement: Studies employ varied, often non-validated assessment tools administered at inconsistent time points, limiting comparability[28].

Long-Term Studies and Adult Outcomes

Longer-term studies of adult transgender populations yield more sobering findings:

A Swedish total-population study spanning 1973-2003 found that transitioned adults had markedly increased morbidity and mortality, including substantially elevated suicide rates compared to cisgender controls, even decades post-transition[29].

Multiple systematic reviews note that none of the studies convincingly demonstrate enduring psychological benefits beyond short-term follow-up[30][31].

A narrative review concluded: "The longest-term studies, with the strongest methodologies, reported markedly increased morbidity and mortality and a persistently high risk of post-transition suicide among transitioned adults"[30].

Important context: High rates of adverse mental health outcomes in transgender populations are multifactorial, involving societal stigma, discrimination, minority stress, and often pre-existing psychiatric comorbidities. Attributing causation solely to treatment effects or lack thereof oversimplifies complex psychosocial dynamics. However, the lack of clear evidence for long-term mental health improvements from medical interventions alone remains a significant concern[18][30].

Shifts in International Clinical Practice

Systematic evidence reviews conducted by public health authorities in several European countries have resulted in policy changes:

Finland (2020): Shifted from affirmative care model toward more cautious approach, emphasising psychotherapy and treatment of comorbidities[32].

Sweden (2022): Restricted GAHT for minors following systematic review concluding risks outweigh potential benefits for most youth[32].

England (2024): The Cass Review, commissioned by NHS England, concluded that the evidence base for paediatric gender services was "remarkably weak" and recommended a more conservative, individualised approach[33].

These reviews consistently identified insufficient evidence quality to support routine medical intervention for youth, concluding that risk-benefit ratios range from "unknown to unfavorable"[30].

Conclusion

The evidence regarding gender-affirming hormone therapy presents a complex and contested picture. Certain physiological effects are well-documented: transfeminine individuals face increased cardiovascular and thromboembolic risks, particularly with oral oestrogen formulations, whilst transmasculine individuals experience haematological changes and atherogenic lipid profiles. These risks necessitate careful patient selection, informed consent, and ongoing cardiovascular monitoring.

Mental health outcomes remain far more uncertain. Whilst short-term studies suggest reductions in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation following GAHT initiation, the evidence base suffers from severe methodological limitations: high risk of bias, short follow-up periods, lack of adequate controls for confounding factors, and inconsistent outcome measurement. Long-term studies of adult populations have not demonstrated convincing enduring mental health improvements, and some indicate persistently elevated morbidity and mortality.

Multiple European health authorities, following systematic evidence reviews, have concluded that current evidence is insufficient to support routine medical intervention for gender dysphoria in youth, recommending more cautious, individualised approaches that prioritise psychological support and treatment of comorbidities.

This does not mean that GAHT is never appropriate or that no individuals benefit. Some patients report significant satisfaction and improved quality of life. However, the combination of documented physiological risks, uncertain long-term mental health benefits, and methodologically limited evidence suggests that more rigorous research, careful patient selection, comprehensive informed consent, and cautious clinical practice are warranted. The current evidence base does not support characterising GAHT as unequivocally beneficial or as standard preventative care for all individuals with gender dysphoria.

References

Iwamoto SJ, Defreyne J, Rothman MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease and feminizing gender-affirming hormone therapy: Implications for the provision of safe and lifesaving care. Clin Endocrinol. 2023;98(6):704-716. DOI: 10.1111/cen.14904

Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23(Suppl 1):S1-S259. DOI: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2017-01658

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Gooren LJ. The treatment of adolescent transsexuals: changing insights. J Sex Med. 2008;5(8):1892-1897. DOI: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00870.x

Puckett EM, Lopez-Esquibel P, Keefe-Oates B, et al. Gender-affirming hormone therapy and impacts on quality of life: a narrative review. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1378232. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1378232

Jasuja GK, Wolfe HL, Reisman JI, et al. Hormone Therapy: Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy. StatPearls. 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544308/

Hughes LD, King D, Gamarel KE, et al. Adolescent Gender-Affirming Medication Use in Insurance Claims Data, 2018-2022. JAMA Pediatr. 2025;179(2):178-182. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.5022

Connelly PJ, Marie Freel E, Perry C, et al. Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy, Vascular Health and Cardiovascular Disease in Transgender Adults. Hypertension. 2019;74(6):1266-1274. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13080

Irwig MS, Shurbaji S, Mahboob R. The effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on cardiovascular and skeletal health: A literature review. Metabolism. 2022;128:154971. DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154971

Nota NM, Wiepjes CM, de Blok CJM, et al. Occurrence of Acute Cardiovascular Events in Transgender Individuals Receiving Hormone Therapy. Circulation. 2019;139(11):1461-1462. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038584

Goldstein Z, Khan M, Reisman T, Safer JD. Managing the risk of venous thromboembolism in transgender adults undergoing hormone therapy. J Blood Med. 2019;10:209-216. DOI: 10.2147/JBM.S166780

Getahun D, Nash R, Flanders WD, et al. Cross-sex Hormones and Acute Cardiovascular Events in Transgender Persons: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(4):205-213. DOI: 10.7326/M17-2785

Alzahrani T, Nguyen T, Ryan A, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Myocardial Infarction in the Transgender Population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(4):e005597. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005597

Spanos C, Grace JA, Leemaqz SY, et al. Impact of Gender-Affirming Hormonal Therapy on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Transgender Health: An Updated Meta-Analysis. JACC Adv. 2024;3(11):101265. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.101265

Vita R, Settineri S, Liotta M, et al. Changes in hormonal and metabolic parameters in transgender individuals: A cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1190. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17041190

Caceres BA, Jackman KB, Edmondson D, Bockting WO. Assessing Gender Identity Differences in Cardiovascular Disease in US Adults: An Analysis of Data From the 2014-2017 BRFSS. J Behav Med. 2019;42(2):231-239. DOI: 10.1007/s10865-018-9992-z

Denby KJ, Cho L, Toljan K, et al. Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk Markers in Transgender Persons Receiving Hormone Therapy. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8(5):520-524. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2023.0166

Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):412-436. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00684-X

James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. Available from: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental Health Outcomes in Transgender and Nonbinary Youths Receiving Gender-Affirming Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

Green AE, DeChants JP, Price MN, Davis CK. Association of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy With Depression, Thoughts of Suicide, and Attempted Suicide Among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(4):643-649. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.036

Collier KL, Hughto JMW, Kaplan SC, et al. Mental Health Changes in US Transgender Adults Beginning Hormone Therapy Via Telehealth: Longitudinal Cohort Study. JMIR Form Res. 2025;9:e66168. DOI: 10.2196/66168

Nguyen HB, Chavez AM, Lipner E, et al. A systematic review of psychosocial functioning changes after gender-affirming hormone therapy among transgender people. Nat Hum Behav. 2023;7(8):1320-1331. DOI: 10.1038/s41562-023-01605-w

Restar A. Misrepresentations of evidence in "gender-affirming care is preventative care" – Authors' reply. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;24:100581. DOI: 10.1016/j.lana.2023.100581

Marques IR, Cagigal CAM, Ezzeddine R, et al. Suicide-Related Outcomes Following Gender-Affirming Treatment: A Review. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e36425. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.36425

Baker KE, Wilson LM, Sharma R, et al. Hormone Therapy, Mental Health, and Quality of Life Among Transgender People: A Systematic Review. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(4):bvab011. DOI: 10.1210/jendso/bvab011

Russell ST, Pollitt AM, Li G, Grossman AH. Chosen Name Use Is Linked to Reduced Depressive Symptoms, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicidal Behavior Among Transgender Youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(4):503-505. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003

Marques IR, Cagigal CAM, Ezzeddine R, et al. The Impact of Gender-affirming Surgeries on Suicide-related Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42262. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.42262

Dhejne C, Lichtenstein P, Boman M, et al. Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: cohort study in Sweden. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16885. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016885

Levine SB, Abbruzzese E, Mason JW. Current Concerns About Gender-Affirming Therapy in Adolescents. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2023;15(2):113-123. DOI: 10.1007/s11930-023-00358-x

White Hughto JM, Reisner SL. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Hormone Therapy on Psychological Functioning and Quality of Life in Transgender Individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):21-31. DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2015.0008

Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine (SEGM). Finland becomes first country to call for evidence-based medicine in treatment of gender dysphoria. 2020. Available from: https://segm.org/Finland_deviates_from_WPATH

Cass H. Independent review of gender identity services for children and young people: Final report. NHS England; 2024. Available from: https://cass.independent-review.uk/