CRISPR Gene Editing Proliferates

CRISPR — standing for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats — is a type of DNA sequence found in prokaryotic organisms. These sequences are derived from DNA fragments of viruses that previously infected the bacteria, forming part of an adaptive immune system. The bacterial CRISPR-Cas9 antiviral defence system has been adapted as a genetic engineering tool, allowing precise modification of genomes in living organisms.

From Bacterial Defence to Genetic Scissors (1987–2012)

CRISPR sequences were first observed in 1987 by Japanese scientist Yoshizumi Ishino and colleagues whilst studying E. coli, though their function remained unclear[1]. The term "CRISPR" was coined in 2002, and by 2005 researchers proposed these sequences constituted a bacterial immune system against viruses[2].

The transformative breakthrough came in 2012 when Emmanuelle Charpentier (Umeå University) and Jennifer Doudna (UC Berkeley) demonstrated that CRISPR-Cas9 could be reprogrammed to cut any DNA sequence at predetermined sites[3]. Working independently, Virginijus Šikšnys at Vilnius University reached similar conclusions[4]. This convergence of discovery—simplifying bacterial defence into programmable "genetic scissors"—earned Charpentier and Doudna the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded less than eight years after their initial publication[5].

Rapid Commercialisation and Market Expansion

A pivotal milestone occurred in December 2023 when both the FDA and European Medicines Agency approved Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), the first CRISPR-based therapy for treating sickle cell disease and beta-thalassaemia[8]. As of 2025, more than 40 CRISPR-based medicines are in active clinical trials worldwide[9]. The technology has evolved beyond Cas9 to include base editing, prime editing, and alternative systems (Cas12, Cas13) offering improved precision and reduced off-target effects.

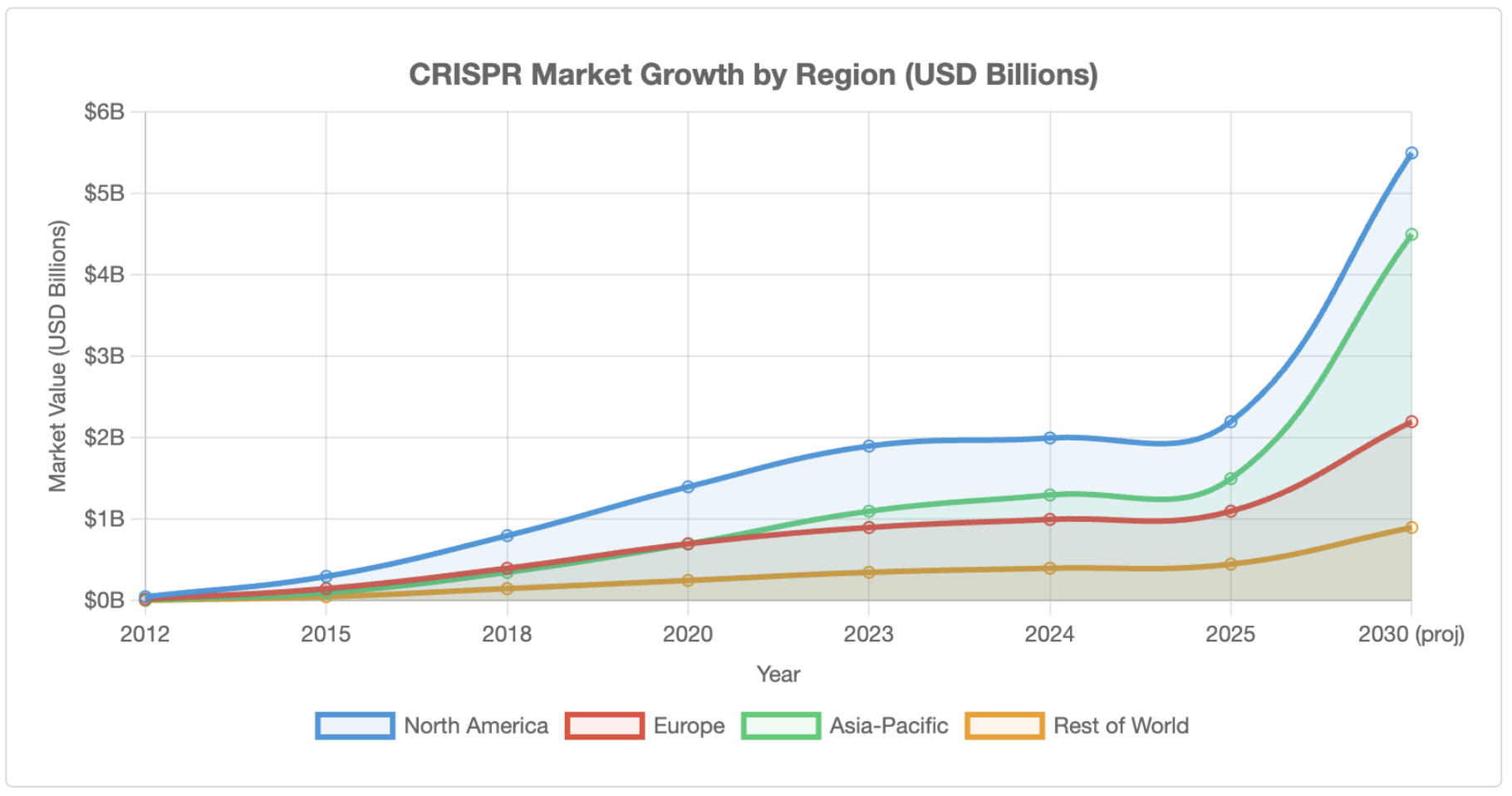

Applications span biomedicine (representing 56–82% of the market), agriculture (CRISPR-edited crops are being commercialised in several jurisdictions), industrial biotechnology, and environmental applications[10]. North America dominates with 41–48% market share, whilst Asia-Pacific shows the fastest growth rates, particularly in China, India, and Japan.

Divergent Regulatory Philosophies

Global regulatory approaches to CRISPR reveal fundamental disagreements about risk, precaution, and innovation. These differences are starkly illustrated by comparing European and Chinese frameworks.

The European Union and France have adopted restrictive policies rooted in the precautionary principle. France ratified the Oviedo Convention, which permits genome modifications only for preventive, diagnostic, or therapeutic purposes, explicitly prohibiting any modification "in the genome of any descendants"—effectively banning germline editing[11]. A 2018 European Court of Justice ruling classified gene-edited crops under existing GMO directives, subjecting them to stringent process-based regulation regardless of whether foreign DNA is introduced[12].

China presents a more complex picture. Whilst guidelines dating to 2003 prohibited germline editing, enforcement was inconsistent, and institutional review boards could approve trials without national oversight. This regulatory gap enabled the controversial 2018 case when researcher He Jiankui created the first gene-edited babies—twin girls modified for HIV resistance—provoking international condemnation[13]. He was subsequently imprisoned for three years. China responded by classifying gene editing as "high-risk" technology requiring State Council approval[14], though its approach to somatic cell editing and agricultural applications remains comparatively permissive, employing product-based rather than process-based regulation.

This regulatory divergence creates uneven commercial landscapes, potential for "CRISPR tourism," and questions about equitable access to transformative therapies.

The Role of AI in Genomic Safety

Whilst public attention has focused intensely on artificial intelligence, CRISPR gene editing arguably presents more immediate and irreversible risks. Editing errors—particularly in germline cells—could propagate through generations. Off-target effects remain incompletely understood, and the full consequences of genetic modifications may only manifest years later.

Paradoxically, AI may prove essential for making CRISPR safer. The complexity of the genome and epigenome exceeds human analytical capacity: understanding how a specific edit will interact with thousands of genetic and epigenetic regulatory elements, across different cell types and developmental stages, requires computational power that only AI can provide. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to predict guide RNA efficacy, identify potential off-target sites, and model downstream consequences of genetic modifications[15]. As CRISPR applications expand, robust AI-assisted safety assessment frameworks will be essential—not to restrict innovation, but to ensure it proceeds responsibly.

References

Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J Bacteriol. 1987;169(12):5429-33.

Mojica FJM, Díez-Villaseñor C, García-Martínez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005;60(2):174-82. DOI: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3

Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816-21. DOI: 10.1126/science.1225829

Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(39):E2579-86. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1208507109

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2025. Available from: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2020/press-release/

CRISPR Gene Editing Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report. Grand View Research; 2024. Available from: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/crispr-based-gene-editing-market-report

CRISPR Technology Market Growth Analysis. MarketsandMarkets; 2025. Available from: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/crispr-technology-market-134401204.html

European Medicines Agency. First medicine using CRISPR technology recommended for approval. EMA Press Release; 2023 Dec. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/first-medicine-using-crispr-technology-recommended-approval

CRISPR-Based Gene Editing Market Research Report. Custom Market Insights; 2025. Available from: https://www.custommarketinsights.com/report/crispr-gene-editing-market/

CRISPR Technology Market Analysis. Mordor Intelligence; 2025. Available from: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/crispr-technology-market

Council of Europe. Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Oviedo Convention). 1997. Available from: https://www.coe.int/en/web/bioethics/oviedo-convention

Callaway E. CRISPR plants now subject to tough GM laws in European Union. Nature. 2018;560(7716):16. DOI: 10.1038/d41586-018-05814-6

Cyranoski D, Ledford H. How the genome-edited babies revelation will affect research. Nature. 2018;564(7736):293-4. DOI: 10.1038/d41586-018-07559-8

Normile D. China tightens its regulation of some human gene editing, labeling it 'high-risk'. Science. 2019 Feb 26. DOI: 10.1126/science.aax0367

Schmitt K. Prime Editing Enters the Clinic. Nature. 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00123-4